In our examples so far, we've known how much data there is in the worksheet. But in RL, the amount of data changes from day to day. For example, you have 280 sales records on Monday, 318 on Tuesday, 278 on Wednesday, and so on. You have to write programs that can deal with that.

What ends the data?

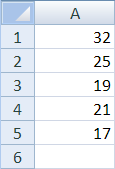

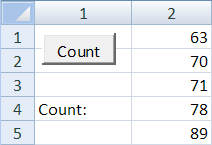

Here's a typical column of data:

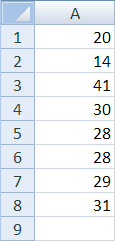

And another:

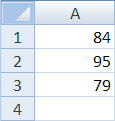

And another:

After a while, the data just stops. There's an empty cell after the data. Hmm… how about we read the data until we get to an empty cell?

We can't use a For-Next for that. Remember the general form:

For [index variable] = [start] To [end]We don't know what [end] is. But we can use a regular Do loop.

Counting rows

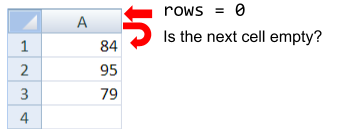

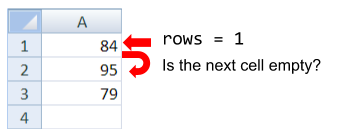

Let's have a variable rows, that we initialize to zero. Then ask: is the next cell (rows + 1 = 1) empty?

No, so add 1 to rows (it's now 1) and keep going. This is look ahead. We decide what to do, based on what the next value is.

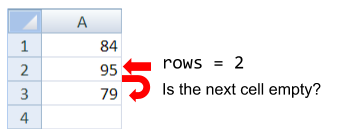

rows is 1. Is the next cell (rows + 1 = 2) empty?

No, so add 1 to rows (it's now 2) and keep going.

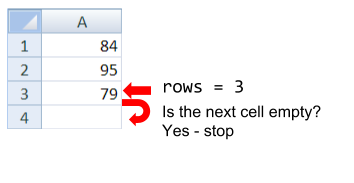

rows is 2. Is the next cell (rows + 1 = 3) empty?

No, so add 1 to rows (it's now 3) and keep going.

rows is 3. Is the next cell (rows + 1 = 4) empty?

Yes, the cell is empty, so stop the loop. rows is 3. That's how much data we have.

Here's code for it.

Line 4 shows the look ahead. Instead of Cells(rows, 1), it tests Cells(rows + 1, 1), looking ahead one cell.

There's something else different about the Do. Previously, we've seen loops like this:

Do

[code]

Loop Until [logical expression]Do

[code]

Loop While [logical expression]These are post-tested loops, that is, the test is at the end of the loop. The [code] always executes at least once.

There are also pretested loops, where the test is at the start of the loop.

Do Until [logical expression]

[code]

LoopDo While [logical expression]

[code]

LoopIt's possible that [code] won't execute at all. For example:

The loop body will never execute.

That might happen in our find-the-end-of-the-data program. Here's the code again:

Suppose there's no data at all, that is, Cells(1, 1) is empty. What's the code going to do? Line 3 initializes rows to zero. The While loop's test fails, because Cells(rows + 1, 1) is "". The loop doesn't run even once. When line 7 outputs rows, it outputs 0, the correct value.

Which loop form should you use? Pretested, post-tested, While, Until… Use whichever makes the most sense to you, for the task you're working on. If the program is easier to understand when you use a post-tested loop, use that one.

Processing while counting

You can do other computations while finding the last element. For example:

This works for totaling, but highest and lowest are a bit messier. So is validation. So is filtering, that we'll get to later. In fact, the more processing you mix in with the counting code, the more confusing things get. More bugs. More screaming.

Thunking

To keep from screaming, split processing up. Remember IPO? That's the input-processing-output pattern.

Replace input with counting, and it works quite well.

Let's write a program that reads an unknown amount of data and computes the total, highest, and lowest values. Let's add some validation: it won't run if there's fewer than 2 pieces of data.

Here's the main program:

All countDataCells does is, er, count the data cells. It returns the number of cells, and a flag showing whether everything went OK. If it didn't, the program stops.

Here's the code for the sub:

Lines 8 to 10 are the look ahead loop we saw before. The countOK flag is set to True (line 12). It's switched to False only if there's a problem with too little data.

Once we have a count, what's next? Here's part of the main program again:

We send rows into computeStats, and it sends back total, highest, and lowest:

Hey! Now that we know how many data elements there are, we can use a For-Next loop. Woohoo! Just copy the code from before.

The main program again:

We send rows, total, highest, and lowest into outputStats:

Thunking the program makes it easier to write, test, and read. For example, when we write countDataCells, we only have to think about counting cells. Toss the stats and output stuff out of our heads, for now. Simpler code. Fewer bugs. Less screaming.

We can also have different people write the subs, then put the whole thing together.

We can replace one of the subs, without touching the others. For example, suppose The Boss wants the output to show in message boxes. Easy peasy.

Nothing else changes. We don't have to think about, test, debug, or scream about the rest of the program.

Let's thunk

From now on, let's organize our code in chunks like this. Our programs are going to get more and more complex. Thunking will keep the complexity under control. Less screaming.

That's a Good Thing.

Exercises

Add code that counts the number of data values in column 2, and shows the count in row 5, column 1. The usual coding standards apply.

Upload your workbook.

(If you were logged in as a student, you could submit an exercise solution, and get some feedback.)

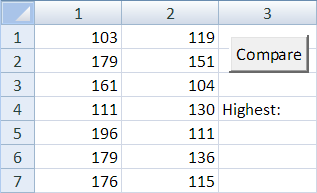

The first column has sales for the north region. The second has sales for the west region. The number of sales in each column might be different.

Write a program that will total the first column and the second. If the first column is higher, output "North" in row 5, column 3. If the second is higher, output "West". If they are the same, output "Equal".

Some of the code has been given for you. Use the code, without change.

The usual coding standards apply.

Upload your workbook.

(If you were logged in as a student, you could submit an exercise solution, and get some feedback.)

Summary

So far, we've known how much data there is in the worksheet. But in RL, the amount of data changes from day to day. We can't use a For-Next loop, because we don't know where to end.

We can use a regular Do loop, with look ahead. We decide what to do, based on what the next value is.

The more processing you mix in with the counting code, the more confusing things get. A way around this is to split processing up. Thunking the program makes it easier to write, test, and read. We can also have different people write the subs, then put the whole thing together.